Behind the Scenes of 'The War Is Here: Newark 1967' – an Interview with the Public Library Association

Public Libraries Online speaks with Chris Campion, editor of The War is Here, about what makes Bud Lee’s photographs so extraordinary, how the events of 1967 in Newark resonate with the current climate, and ensuring that the personal stories of the people affected are told.

BY BRENDAN DOWLING

This interview first appeared in Public Libraries Online on May 31, 2023.

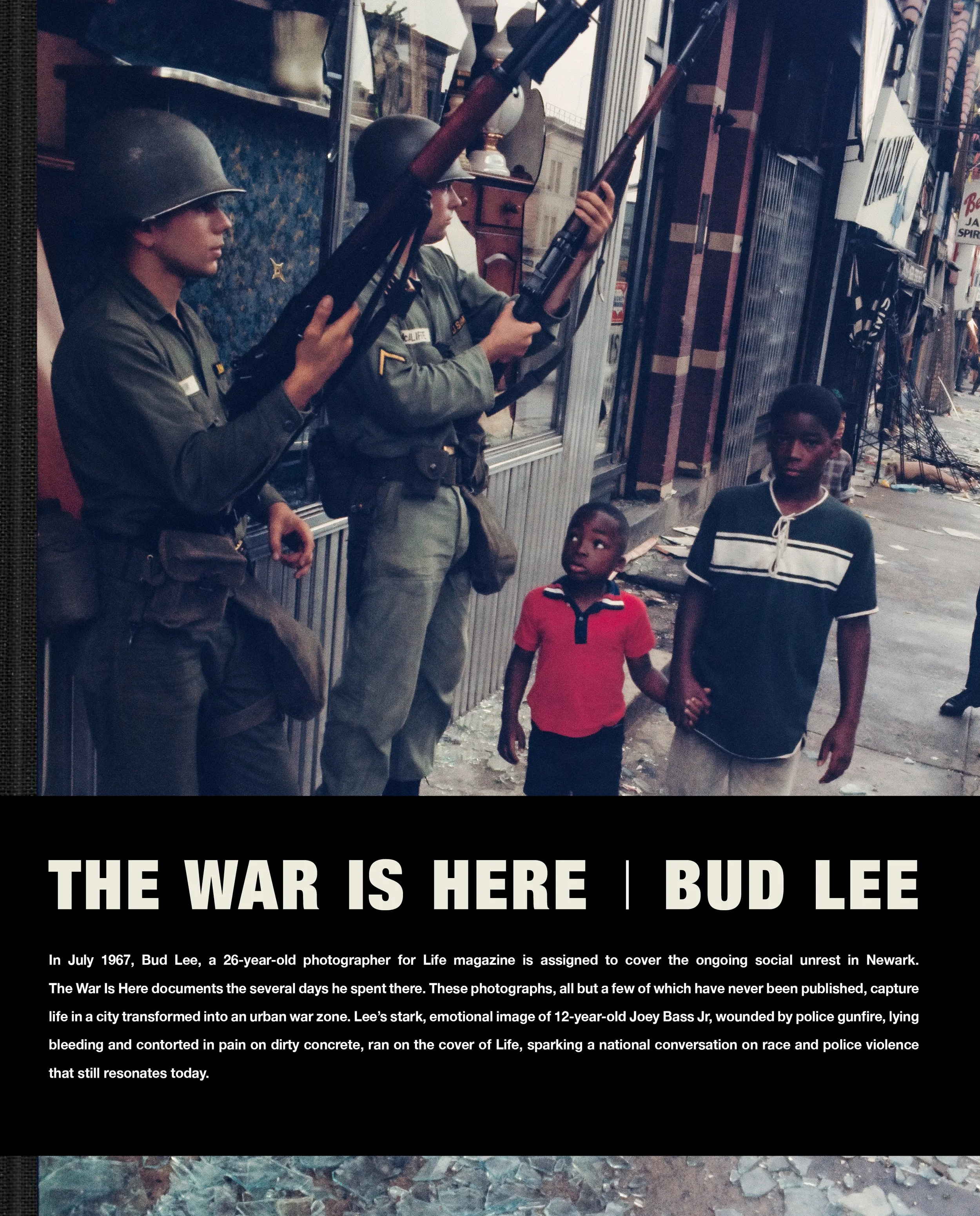

In July 1967, Newark citizens took to the streets to demonstrate against the arrest and beating of a young Black cab driver by police. Five days of protest followed, leaving twenty-six people killed by police gunfire, thousands arrested, and millions of dollars incurred in property damage. The War Is Here collects unforgettable photographs Bud Lee took on assignment for Life magazine, capturing the lives of ordinary citizens as their neighborhoods were transformed into war zones. We spoke to the book’s editor, Chris Campion, about what makes these photographs so extraordinary, how the events of 1967 in Newark resonate with the current climate, and ensuring that the personal stories of the people affected are told.

Can you start by giving us a brief overview of the events that the book covers?

The photographs in the book depict events that occurred over five days in Newark. I believe that the uprising began on July the 12th 1967. It was sparked by the arrest and beating of a Black cab driver named John Smith. Essentially the spark that lit the fuse for this uprising was the arrest and the beating of John Smith, who was held in a precinct. People in the community did not know what was happening to him, but they had heard that he had either being killed—which he had not—or his ribs had been separated from the beating that he received from the police. There were protests outside the police precinct that gradually got larger and the situation grew and grew till there was looting and stores being burned. This happened for two days, I think July 13th through the 14th. In the early hours of July 14th, there was a call from the police chief and the mayor of Newark, Hugh Addonizio, to the Democratic governor, Richard J. Hughes, basically telling them that the situation had gotten out of control and they needed to call in the National Guard. So Governor Hughes gave the order to call in the National Guard.

Photograph: Bud Lee

The troops came into the city and set up roadblocks and curfews to try and control the movement of people and police the situation. That happened, I think, on July 14th. By that time there was a curfew in the city. That’s where Bud Lee comes into the story. He received a call, I think on July 14th, that he needed to go to Newark immediately to cover what was happening there for Life magazine. The book really covers that period. It’s the aftermath of the first two days of what was occurring in Newark, which was the most violent and explosive [time]. In some senses what you’re seeing, although Life had tasked Bud Lee with going to cover a “riot,” what he actually captured was the aftermath, although the events carried on for another three days. He’s sort of almost capturing this vacuum after the explosion. To me, that’s what’s so powerful about these images. They’re really detailing people trying to live their daily lives in what had become a war zone.

The centerpiece of the book are the photos that Life chose to run that he took. That was an event that he sort of stumbled onto and became involved with, which was the shooting and killing of a man named Billy Furr by Newark police and the wounding of a young twelve-year-old boy named Joey Bass Jr. The photo of Joey Bass Jr. lying wounded by police gunfire on concrete on the streets of Newark is what ended up on the cover of Life magazine. The photos of the killing of Billy Furr by the police were inside the magazine

Can you give a little background on Bud Lee? He seemed to have a unique background that made him uniquely suited to take such memorable photos here.

Suited and not suited at the same time. He was essentially a self-taught photographer. He had trained as an artist at the National Academy of Fine Arts at Columbia University. He was a fine artist. He was a painter. He studied under a man named Dean Cornell, who was a muralist and had been referred to as the Norman Rockwell of murals. Photography wasn’t Bud Lee’s first choice as a medium. He enrolled in the military. While he was in the military, he took a photography course and he became a photographer for Stars and Stripes magazine, in Europe, largely. This was early ‘60s.

He came back to America and won Military Photographer of the Year, but they weren’t for combat photos. They were photos of soldiers in training. He had used as his model for those photos a fashion photographer named Hiro who worked for Harper’s Bazaar. They were sort of staged photos, but very powerful. When he won the Military Photographer of the Year Award, he was basically headhunted by Life magazine’s Photo Editor Peggy Sargent and so he started working for the Life magazine in 1967.

Bue Lee’s press card

What he brought to the photographs that he took in Newark was a very particular aesthetic that came out of his fine arts training. When I look at these photos, they don’t feel like news photos necessarily. There are aspects of that to them, but there’s something about the framing of them, the focus on people and characters. All of the photos in the book are run full frame. There’s no cropping on anything. Some of the ways that they were framed were pretty extraordinary considering he was shooting in the moment. Often there were only single shots. There were not multiple shots of the same event, or the same people even. He brought a sort of an artist’s eye to documentary photography. I think that really shows in his approach and his empathy for the people of Newark and his subjects. Obviously, you know, he’d sort of stumbled into this situation, in some ways. It wasn’t his first choice thing to do. It was an assignment.

A lot of the pictures have almost this painterly feel to them.

Certainly in the choice of images. I was very conscious of that. There’s a stillness to them because of that. There are action photographs that are in there, but I think some of the more powerful images and the more emotive ones are these very beautifully composed photographs. One in particular is the photograph of Joey Bass’ family sitting in their house. My art history background is not very good, but it sort of feels like a Renaissance painting in some ways.

The other part of that is because of his fine art training, he could call on references to classic paintings. We’ve found paintings that he almost sort of recreated in his head through the lens in the spur of the moment, which to me was pretty extraordinary. He just had that vision, that focus, and also that art history knowledge that he could see something in the situations that he was covering, and translate it and utilize classic paintings as a sort of model for what he was trying to capture. I find it very hard to explain because he was doing this stuff in the moment. There was something about what he was seeing that he was able to translate into his images, if that makes sense.

Another fascinating aspect of the photos was that two of his cameras had been damaged, so when he was actually taking pictures he only had the one shot to get the image.

That came into play specifically in the sequence of images of the shooting of Billy Furr. He’s suddenly in this situation where he’s having to take photographs in a split second. There’s all of these things happening in front of him and he’s trying to shoot. He had a Pentax Spotmatic camera with a manual wind on it. Basically what happened was he met this twenty-four year-old man named Billy Furr on the street, and he and the reporter Dale Whitner started talking to Billy and his friends.

Billy and his friends decided to go into an already looted liquor store and get some beer because it was a hot Saturday afternoon. Bud took photos of that occurring, so there were photos of Billy Furr and his friends going into this store and carrying out cases of beer. What happened next was that the police arrived without warning. A patrol car just comes screeching to a halt on the sidewalk. The cops jump out. Two of Billy Furr’s friends basically fall to the sidewalk. Billy goes running with a six pack in his hand. What you see in the images is the cops aiming and firing and shooting him in the back. Bud was capturing all of this. Two of those shots that they fired at Billy Furr ended up hitting this twelve-year-old boy named Joey Bass at the next intersection.

Photograph: Bud Lee

So Bud moves between taking photographs of Billy Furr who is now fatally injured and dying on the sidewalk and capturing the crowd of onlookers that are surrounding Joey Bass Jr., [plus] the police coming in and attending to him with paramedics. It’s an extremely dramatic sequence of images. I think six of them might have been used in Life. I’m not sure how many there are, maybe twenty-four images total. But those images that run in the central section of the book, we used pretty much every image he shot.

I separated it from the rest of the book because I really wanted people to be in that moment with Bud. I wanted you to be able to experience this as it was happening and really sit and dwell on how this event occurred. I think they’re very powerful images and they’re images that need to be seen, especially in the current climate where these things are happening on a daily basis. I feel a lot of the images in this book, as well as being a historical document, really speak to the current place that we’re in in America. Things that are occurring with gun violence, with police brutality, with any of these situations that are coming up. I just felt it was very important that these particular images are seen and exposed. To me, they offer a sense of perspective. We’re in the same place that we were fifty years ago in some regards. There’s a certain amount of police accountability now, but these things are still happening. When I was looking at these images, it was deeply shocking to me that we’re sort of in the same place.

I don’t want to psychoanalyze Bud, but it seems that he was profoundly affected by his experience in Newark. He visited Joey in the hospital for months afterwards, right?

Yeah, that’s true. He was affected in the way that war photographers are affected. That’s the only way that I can understand it, I think. I quoted him in the book, specifically about the incident with Billy Furr and Joey Bass, he said that he didn’t feel in danger, he felt like the camera was a shield. I wrote that it wasn’t a shield for the mind, because you’re still witnessing these images. He’s taking photographs, he’s frozen behind the camera. He can’t act. He can’t intervene, which is something that I cited Susan Sontag talking about, the quandary that a photographer faces in these situations. You either intervene or you take a photograph, and the photographer is almost compelled to take the photograph. But the impact of those events, witnessing those events, being involved in those events, and the level of guilt that he felt—because he had taken photographs of Billy Furr in the seconds before he was shot and killed by the police—I think that that really stayed with him.

Also, this was the story that made him. He won the News Photographer of the Year award. I think that didn’t sit well with him on some level. These photos of immense tragedy had sort of somehow given him a leg up. Again, it’s like the feelings of guilt I think that were there. So yes, he was profoundly affected by these events.

I appreciated that you included the conversation he had later with a New York Times photographer who pointed out that Billy was probably showing off for Bud by getting the beer, and how Bud’s presence was a factor in how events played out.

I think he was very aware of that. [The fact] that that conversation came from him really shows his awareness of the complexity of all of those events, and his own role in it. That’s the role that most photographers, certainly war photographers and conflict photographers, have to face. That was not where his heart lay. He really was an artist at heart. It was difficult for him to deal with all of that stuff.

The foreword of the book is written by Ras Baraka, the mayor of Newark. Can you talk about the connection his family has with Newark and the events of 1967?

Mayor Baraka’s father was Amiri Baraka, the esteemed poet, playwright, and political activist, who was deeply associated with Newark. At the time of the events of July 1967, Amiri Baraka had just moved from New York back to Newark. He was very much associated with the Greenwich Village arts scene and with Alan Ginsberg. He was a very noted character already. He moved back to Newark and sort of re-established himself there. His house on Sterling Street in Newark became known as the Spirit House and it became a community center and arts workshop. Amiri Baraka became very involved in community work and community activism at that time, so he was well known, if not notorious.

Photograph: Bud Lee

During the uprising in ‘67, almost probably the same day that John Smith was beaten by the police and arrested, Amiri Baraka went out to see what was going on in the city. He and the people he was traveling with in a van were stopped by police also. He was subjected to a police beating that almost killed him. He was arrested and then charged with illegal possession of a firearm, which he maintained had been planted by the police. It turned out later that one of the same policemen who had been involved in the beating of Amiri Baraka was also one of the same policemen who had fired the shots that killed Billy Furr and wounded Joey Bass, which is kind of an extraordinary, almost unbelievable, coincidence.

Amiri Baraka was arrested and then he was released around July 24th, a couple of weeks after the events in Newark. He hosted the first National Conference on Black Power in Newark. There was a press conference at the Spirit House, and H. Rap Brown, who was chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, was there. Ron Karenga of the US Organization in Los Angeles was there. Bud Lee went back to New York to cover the National Conference on Black Power and photographed Amiri Baraka and the other participants in the conference at the Spirit House. Part of that press conference, Bud photographed the family of another young man who had been shot and killed by the police, a nineteen-year-old called James Rutledge, Jr. He had been shot thirty-nine times by police. His father and his mother came to the event and his father held up a photograph of the autopsy that had been performed on James Rutledge, Jr. to show what the police gunfire had done to him. Amiri Baraka spoke about this event and called it “an act past murder.” I think it was really indicative of the level of police brutality and violence that was being meted out on members of the community there.

Those photos basically form the end of the book. The photo of Amiri Baraka, who still had the bandage on his head from the police beating, in this very sort of fiery pose talking, is the last photo in the book. It just felt it was appropriate to end that way. The book actually ends with a quote by Amiri Baraka. So that’s a long way of saying that Ras Baraka’s family were intimately involved in these events.

I think the most powerful thing about Mayor Baraka’s text is he’s talking about generational trauma and how it is handed down. That’s his own family’s trauma, his memory. He was not born yet, but basically the events in Newark became part of family lore, but also the trauma that happened to Newark itself. He talks about sort of managing that trauma and trying to rebuild and reframe [it]. I think his text is extremely powerful. It was an extraordinary thing that his family went from. His father was a political activist and the next generation Ras Baraka had assumed the reins of power in Newark, really carrying on his father’s work. I think that’s an extraordinary arc for the Baraka family. I’m just very grateful that he wrote that text for us. It really does not pull any punches, and really frames the book as something that’s affecting people in Newark, but also around America today.

I think you need that bracing beginning to prepare yourself for the images that you’re going to see too.

It definitely sets the tone. Again, these are not pictures of a riot, so to speak. These are pictures of a people trying to survive in the aftermath and in the face of all of this sort of destruction that had been meted on the city. For me, one of the more powerful images is the second image in the book, which is of an armored personnel carrier with a soldier with a rifle, and in the background are these destroyed buildings. It really spoke to the title of the book, “the war is here.” I’ve showed people that photograph and they think it’s somewhere outside of America, that it’s Vietnam or somewhere like that. It’s hard for them to even process that this was an American city. Again, I think that’s why these images need to be seen. The war is here, the war is continuing. We’re still dealing with these issues. The National Guard is still being sent into American cities. The police are using militarized tactics to police American cities. We’re still dealing with all of these things to this day.

You end the book with this really powerful letter that Billy Furr’s widow, Ellene Furr, wrote last December. Can you talk about what went into the decision to give her the final word in the book?

I had wanted to reach out to her and actually the family of Joey Bass, who we weren’t able to locate. I definitely wanted to reach out to the family of Billy Furr to let them know that the book was being published. I was put in contact with Ellene by Junius Williams, who’s the official historian of Newark, and so I reached out to her, and she responded straightaway. It sounds strange, but it was almost as if she’d been waiting for me to call.

These are events that are long in the past, but had a massive impact on her life. She’d been married to Billy Furr for two years at the time that he was murdered, so she lost her husband. I said, “Would you be interested in writing something for the book?” because I felt it was very important to take this back to the personal stories—especially considering the photos that are in the book, to really bring that back into a personal sphere. I think we forget about the victims of these events.

I should qualify that in some ways. Taking it back to what Mayor Baraka wrote about generational trauma, that was really part of why I wanted to make sure that Ellene’s voice was in there, and that she was able to speak about how these events impacted her. I think when these killings occur, we’re almost caught in an eternal sort of present. We’re sort of trapped in this moment, replaying the events over and over again. Certainly in these days when there is footage of, say, George Floyd’s murder, and this video footage of it gets replayed over and over again. We’re sort of caught in that moment, but I think we need to step outside of that and realize that it doesn’t end when the camera is switched off. I’m finding it hard to describe this, but I wanted to make sure that we understood that these things, these events, have impact that goes through decades. They change people’s lives entirely. They don’t even change one person’s life, I mean, it’s entire families. Anytime there are any of these shootings, Uvalde or Buffalo or wherever it is, we’re talking about tens, hundreds, even more people being impacted by these events and traumatized by them. I wanted to bring that home to somebody’s personal story and explain the impact that these events had on her. It’s a difficult subject to talk about.

Finally, what role have libraries played in your life?

As a writer, and as a journalist, libraries were so important to me, just in terms of research, as a source of knowledge, and being able to go into a library and call up books. I worked in the British Library as well and have done research in there. It’s so important to have that store of knowledge and access to that knowledge as a free resource as well, that you can just go into a place and read books, look at books. The library is a space where there are no restrictions on you in terms of time or access. I think that’s incredibly important now. I’d very much like this book to be in libraries. I think it’s important that it’s sort of sitting there, that people can take the time to sit, look at it, and really absorb the images and the story they’re telling.